Walking into DenHolm’s Melbourne studio, giant slabs of limestone nearly barricade the entrance. Designers Steven John Clark and Lars Stoten note that the stone isn’t usually kept in the doorway, but a large-scale project has forced them to stash the slabs all over the space. Around us loud machinery whirs, studio hands bustle, and sculptural pieces, art as much as furniture, emerge from stone and metal. The works embody Steven and Lars’ foundational desire to design on their own terms, embracing the strange and the imprecise to draw nearer to an unlikely and invigorating beauty.

Steven, who founded DenHolm after working in masonry and attending school for fashion, and Lars, who also got his start in the fashion industry, have created a niche in the industry blurring the lines between stone furniture and sculpture. The founders and their team arrive around 6:15 in the morning every day for a planning meeting where they go through the projects they’re currently working on, monitoring progress from first sculpt to final approval from the client.

- Photo by Annika Kafcaloudis

- Rosa Colada pigment dyed limestone chair. Photo by Annika Kafcaloudis

“The majority of the time we’re reacting to a client getting in contact with us because they like something we’ve already made,” Steven says. “Then that will be the beginning of the conversation.” DenHolm’s clients are primarily interior designers. If they’re after a new piece the studio will work off a mood board, eventually forming something entirely unique. If a client is after something very similar to an existing DenHolm piece the team will use that as a base, but because everything is done by hand Steven says they never make the exact same thing. “We actually can’t. We don’t have the capacity to make exactly the same thing. It’s always iterations—they’re always slightly different.”

Among its upcoming projects DenHolm has been asked to headline a gallery exhibition for this December’s Art Basel Miami Beach. As opposed to the usual client briefs, that project is a bit more about the conceptual. “We’re given a brief, which is pretty much ‘do something mental or do something brilliant,’ and then we put our heads together on that, and Steven does his magic,” Lars says.

- The designers often work with limestone, which exists in abundance just around the corner in South Australia. Photo by Annika Kafcaloudis

- Scattered throughout the studio, designs like Ellie (seen above) reflect DenHolm’s rejection of formulaic design, embracing exploration and spontaneity. Photo by Annika Kafcaloudis

The “heads together” making and experimentation is the team’s favorite part and perhaps even the key to Steven’s so-called magic. The continual iteration gives way to a sense of freeness felt within each piece, as though the works are stirring or reacting to a constantly changing environment.

This same spontaneity and desire for originality spurred DenHolm to build Gazzette—a digital platform described on its pages as “A Liberated Voice Free From PC Mercenaries & Absently Choreographed Content.” Deep diving and navigating the platform is strangely similar to exploring their sculptural pieces; the Gazzette has an unpredictable nature that feeds DenHolm’s exploration of the curious and the surprising. But while the studio’s physical works are typically made to brief, the Gazzette allows them to get deeper and wilder with their mindset around creativity. In it they explore interesting people doing everything from designing knitwear to tiling pools, and dive into their own process as well. “There’s a bit of a madness there. We’re showing that our processes aren’t really processes. They’re all over the place, like the format of the site,” Lars says.

- The Den Holm founders sense of style infuses their work and their wardrobes. Photo by Annika Kafcaloudis

- DenHolm’s designs often embrace asymmetry and imperfection, as in the refined yet rudimentary looking stone supports of the Toorak console limestone table. Photo by Peter Ryle

As a design studio DenHolm purposefully stands on its own—bold in its decision to largely reject the mainstream design discourse, opting out of gallery shows and events within Melbourne’s creative community and choosing to pave its own way without hesitation. Speaking with Steven and Lars, the pair reiterates a commitment to embracing the imperfect to discover what it means to create.

What do you love, or hate, about making a sculpture?

Steven: With sculpture you can have something you really love from one view and then take three steps to the right, and it could be something you really don’t like. The conflict is that if you change that piece, more than likely it will influence the piece you love. Then it becomes a hierarchy of decision-making around what is possible. There’s a game that gets played.

Lars: Yeah, there’s a give and take. You’ve also got the utility of the piece in that equation—is it usable in that format, in that finish? On top of that, with any type of creative application, one thing we always ask is, “Do we want people not to like it?” That’s the other element. Make people a little bit uncomfortable. Make the piece more memorable because it’s not solved automatically. Give them something to think about, another angle to look at it.

- “When we’re working on more of a conceptual piece we get the cooperative element of everybody involved in the studio,” Lars says. Photo by Annika Kafcaloudis

- Photo by Peter Ryle

With the more conceptual briefs, is there a moment when you realize that a piece is finished?

S: When it leaves.

Do you tinker until the end?

L: Yeah, absolutely. The last piece we just put out to London; we were literally tinkering while it was going in the box. I think when we’re working on more of a conceptual piece we get the cooperative element of everybody involved in the studio.

S: Yeah, exactly.

How does that relate to what you’re doing with Gazzette?

S: It’s funny. This is the first time the penny’s dropped a little bit. [Gazzette] is like a piece because there’ll be some functionality to it, it works in a certain way, but then there’s the way it’s laid out. Sometimes it’s not easy for the viewer to understand, but that allows the person to come back and see something new the next time, which I think should always be represented in a DenHolm piece. The idea of somebody walking around a piece and understanding it within one walk around would be a disaster.

“There’s a bit of a madness there. We’re showing that our processes aren’t really processes. They’re all over the place.”

L: You’re right. Each page of the Gazzette should have that to it. As people dip and dive out they get something new every time. I think that’s fun. It’s just the beginning; there’s so much more where it’s going, and its potential is fucking huge. And that’s fun as well.

What’s the main thing you’ve learned from your own work and creative process?

S: More than anything, the essence of it is backing yourself. For years and years it’s Sunday night and you start getting the fear because you’ve got to go back to work. Before you know it you decide not to sleep until one in the morning because you have to watch that TV series. But at the end of day it’s just because you don’t want Monday to come. I haven’t had that feeling for the past six years, and that’s the dream.

- Photo by Peter Ryle

- Photo by Annika Kafcaloudis

L: I had exactly the same thing when I was younger. It really hit me when I was doing my own [fashion] line and they asked me to create a small capsule collection for Topshop. They approached me with a stupid amount, like a design fee. I went into the Topshop offices and the elevator opened on all these tiny little cubicles of people, and from that point on in my career, particularly in terms of creativity, at times I sacrificed money. At times I felt guilty about not taking certain contracts, but I knew that’s where it was ending for me. Creativity, especially in terms of design, is often about relationships—with yourself and with other people as well.

L: It becomes like a relationship, and it’s there and it’s tangible.

S: It’s a good source of memories. It’s like a photo, but it’s captured like a little time capsule.

L: All the emotions and things come back to you. I have that with people I’ve worked with in the past. I look at collections… it’s not about the beauty of the garment. It’s like I can remember the late nights sitting around with close friends and having a curry and being stupid or whatever. Relationships in creativity are quite beautiful, as soppy as it sounds.

- Lars tinkers in the studio. Photo by Annika Kafcaloudis

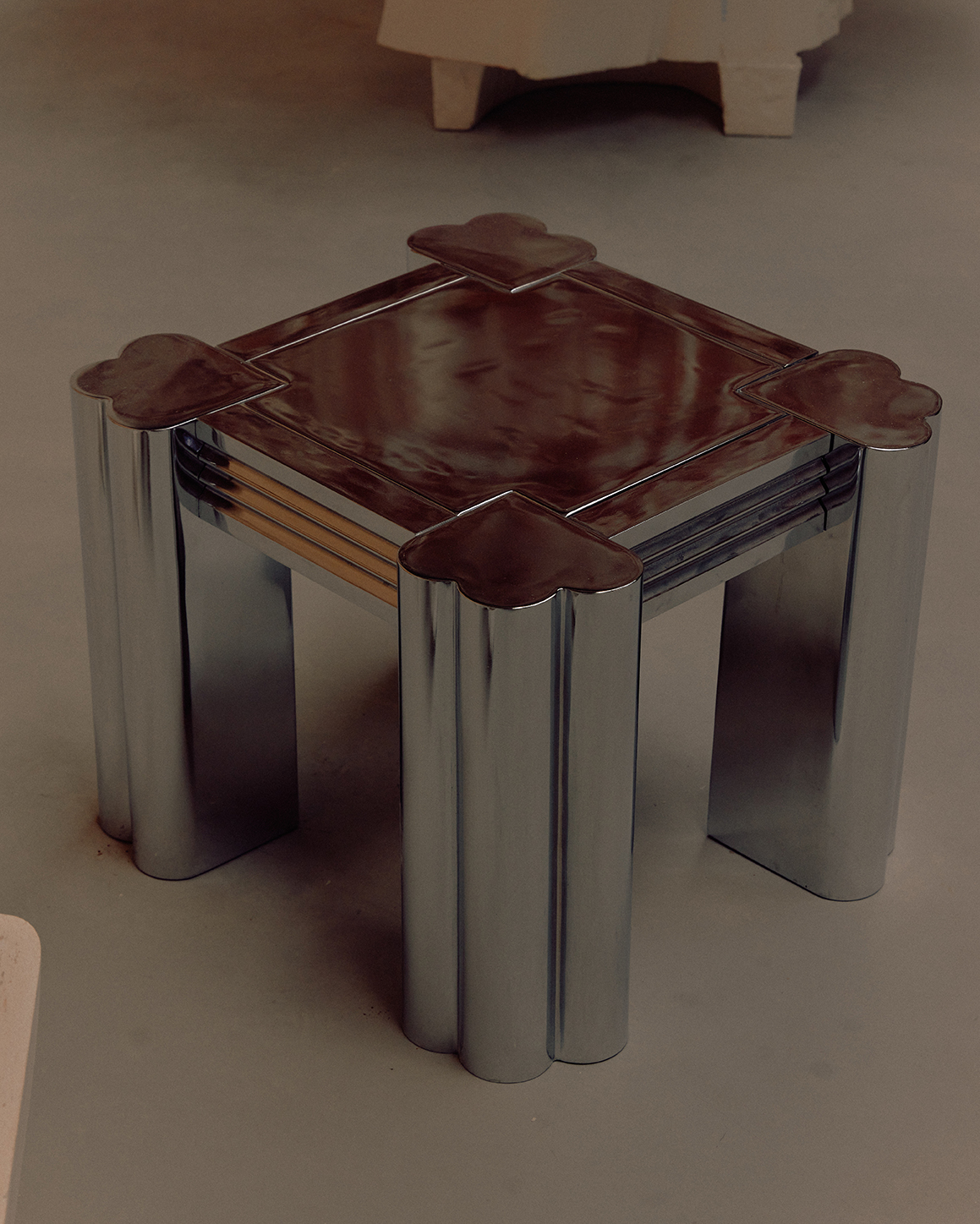

- The DenHolm Idaho chrome side table is handcrafted in stainless steel, built for longevity and timelessness. Photo by Annika Kafcaloudis

Do you have any advice for other creatives out there?

S: This is really easy: Just do. And that’s super complex. The thing is you can’t grow if you’re not moving. It’s impossible. That doesn’t mean making bad decisions constantly, but even bad decisions allow you to grow. Even if it’s going backward first to go forward. Stop looking at fucking Pinterest. Don’t be a copycat. If you’re copying you’re always going to have

to copy.

L: Don’t overthink. As soon as you start thinking about the cost of things, the moment you start hesitating like that or even worse, in my case, thinking “What is someone going to think of this?” you can get frozen by that. Just fucking play. Have fun. Don’t worry about measuring it.

A version of this article originally appeared in Sixtysix Issue 11 with the title “Imperfection in Stone.” Subscribe today.